BDSL2 Language Guide - StateMachines

Most of the depth of BDSL2 is in its handling of StateMachines. A StateMachine is a description of an entity's behavior within the DMK danmaku engine. It involves movement, firing bullets, handling phases, and so on.

Consider this code:

for (var ii = 0.; ii < 3; ++ii) {

Logs.Log("code: " + ii.ToString(), null, LogLevel.INFO);

}

var sm = gtr {

times(3)

} {

exec(b{

Logs.Log("gtr: " + i.ToString(), null, LogLevel.INFO);

})

}

sm;

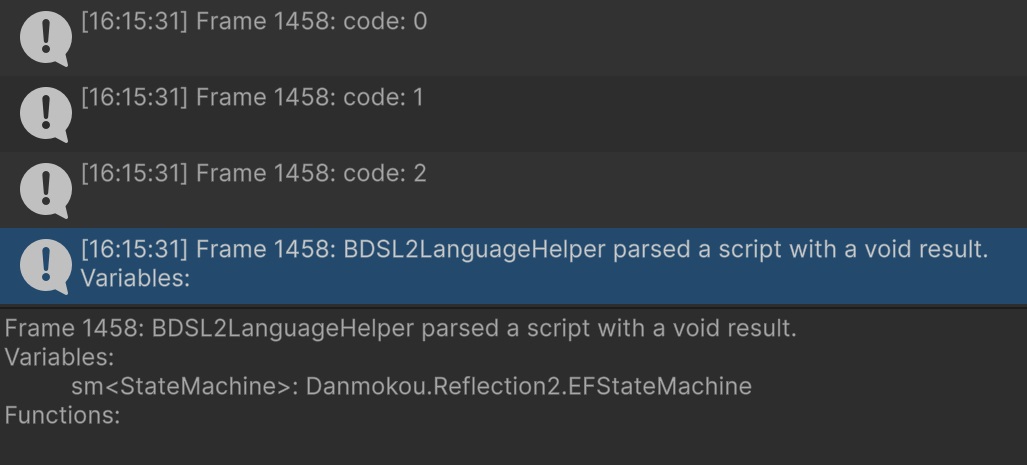

If you set this script on BDSL2 Language Helper, with the target type as void or StateMachine, then this is what you will see in the console:

We see the "code" logs because the for loop is executed when the script is executed. However, the "gtr" logs are only executed when the StateMachine is executed. In order to view the behavior of a StateMachine, you should assign a script to the "Behavior Script" field of a BehaviorEntity and make sure the script returns a StateMachine. In BasicSceneOPENME, you can use the mokou-boss BehaviorEntity.

If we assign this script to the "Behavior Script" field of the mokou-boss BehaviorEntity, and then start Play Mode or press R to reload the scene, then we will also see the "gtr" logs as well:

The usage of gtr/gtrepeat is discussed in the first danmaku tutorial. In short, it is a "repeater object" which functions similarly to a for loop. This document will focus on the semantics of how StateMachines and their internals differ from standard code.

Expression Compilation

The script below is a simple script that fires a single arrow bullet which accelerates to the right.

var a = 5.0;

var v2::Vector2 = new Vector2(a * a, 0);

paction 0 {

position -2 1

sync("arrow-red/w", <0.5;:>,

s(rvelocity(new Vector2(t * t, 0))))

}

In this example, new Vector2(a * a, 0) constructs a Vector2 and assigns it to the variable v2. However, new Vector2(t * t, 0) doesn't do the same thing, even though the code has the same structure. In fact, there isn't any variable t that could even be referenced in this case.

In this code, new Vector2(t * t, 0) is actually treated as a lambda which takes a linked bullet as an argument, and t refers to the parametric time of the linked bullet. It actually has a structure closer to (ParametricInfo bpi) => new Vector2(bpi.t * bpi.t, 0). This lambda is then treated as a Rotational Velocity function, which is why the bullet accelerates with time.

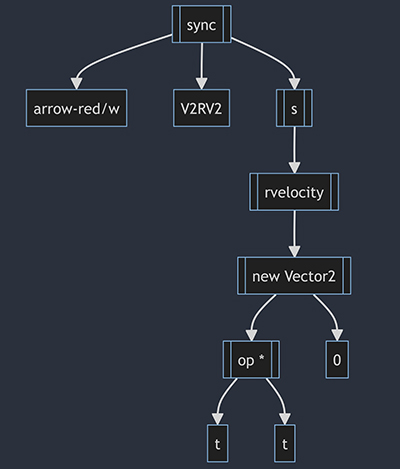

To understand why this difference occurs, consider how the script itself is represented in the backend. It is first converted to an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), which represents the structure of the code in an abstracted way. The diagram below shows the AST for the "sync" StateMachine in the above script.

If we want to execute this code, we need to compile this AST into a delegate (like a Func<...>), and then execute that Func. The BDSL2 Language Helper MonoBehavior compiles the provided script AST into the ScriptFn<T> delegate, which returns a value of type T. BehaviorEntities compile their scripts into a ScriptFn<StateMachine>, then run this once to obtain the StateMachine, which can be executed at a later time.

However, we could also theoretically compile any subtree in this AST if we wanted to. For example, we could take the string "arrow-red/w" and compile it into a Func<string>. In fact, if we had a script with just the contents "arrow-red/w" and we asked the BDSL2 Language Helper to compile it into type "string", then it would compile the script AST into a ScriptFn<string> delegate and execute that.

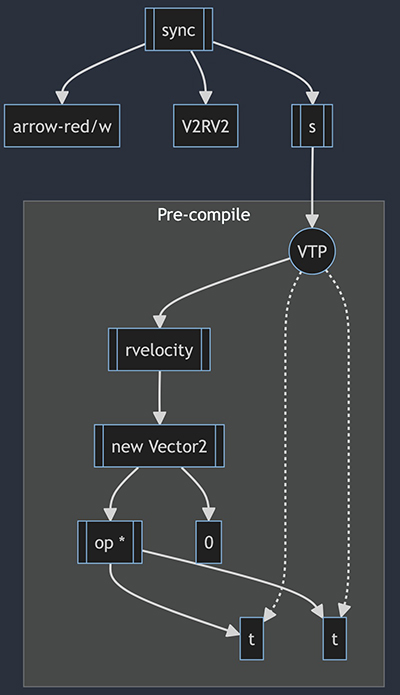

In this case, the s function takes a VTP argument. A VTP is a delegate which, loosely speaking, takes a bullet and delta-time as arguments and determines how the bullet should be moved. However, the method rvelocity doesn't return a VTP. Instead, it returns a special value which can be compiled into a VTP. In order to bridge this gap, the backend pre-compiles the part of the AST below s, converting it into a VTP that can be provided as an argument to s. This compilation step also provides t as an implicit argument, since the VTP delegate takes a bullet as an argument, and the bullet has a time variable.

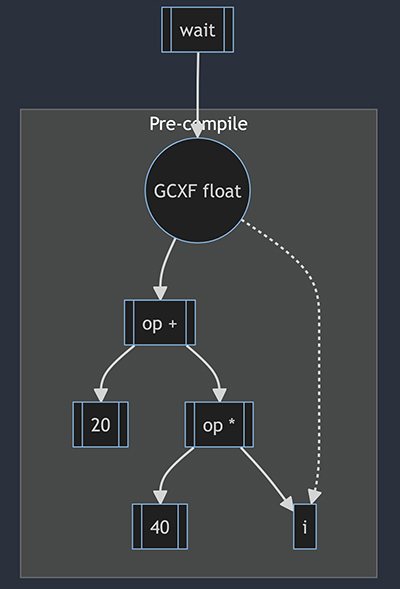

The other most common usecase for expression compilation is in repeater properties. Consider the below script:

async "arrow-red/w" <> gcr {

wait(20 + 40 * i)

times(4)

} s rvelocity(cx(2))

In this example, four bullets are fired, with a delay in between. The delay gets longer for each bullet. This occurs because i refers to the loop iteration of the gcr repeater. In this case, the expression 20 + 40 * i gets pre-compiled into a GCXF<float> delegate, which is basically the same as Func<GenCtx, float>. The i is stored within GenCtx.

Lexical Scoping

In BDSL2, any block forms its own lexical scope. Variables declared in a lexical scope are only visible within that scope and its descendant scopes (unless it is declared with hvar, in which case the declaration is moved one scope up).

In addition, repeater functions also create lexical scopes. Consider the below example:

gtr {

wait(20)

times(4)

preloop b{

hvar myVar = 4 - 0.7 * i

}

} {

sync "arrow-blue/w" <> s rvelocity(px(myVar))

}

In this code, gtr creates a lexical scope, which encloses both the repeater properties and the StateMachine array. preloop b{ ... } also creates a lexical scope, since it uses a block. Since we want myVar to be visible to the StateMachine sync, we use hvar so the declaration of myVar is moved into the gtr lexical scope.

We cannot use myVar outside of the gtr. Also, if we did not use hvar, then this code would not compile.

The lexical scopes of repeater functions are limited in that they do not exist at compile-time, only at runtime. What this means any variables declared in them cannot be accessed except in delegates executed at runtime (such as VTP/GCXF). For example, there is a StateMachine called debug which takes a string as an argument. If we tried to do the following:

gtr {

wait(20)

times(4)

preloop b{

hvar myVar = "hello world"

}

} {

debug(myVar)

}

This typechecks, but fails to compile.

ReflectionException: Line 9, Cols 11-16: The variable string myVar (declared at Line 6, Cols 14-19) is not actually visible here. This is probably because the variable was declared in a method scope (such as GCR or GSR) and was used outside an expression function.

If you are using this variable to construct a SyncPattern, AsyncPattern, or StateMachine, then you can wrap that SyncPattern/AsyncPattern/StateMachine using Wrap to make it an expression function.

The reason that this fails to compile is that myVar is only created when GTR is executed, but debug is constructed at compile-time, so myVar cannot be provided as a string argument. It can be provided as a GCXF<string> argument, since that only requires myVar to exist at runtime (when the GCXF is executed).

The print StateMachine takes an argument GCXF<T> and logs it to the console. The following code works as expected, printing "hello world" to the console four times with a slight wait in between:

gtr {

wait(20)

times(4)

preloop b{

hvar myVar = "hello world"

}

} {

print(myVar)

}

We could also use the wrap helper. This takes an argument of type GCXF<StateMachine>. In other words, it constructs the debug StateMachine at runtime, once for every loop of the GTR repeater. (wrap can also be an AsyncPattern or SyncPattern.)

gtr {

wait(20)

times(4)

preloop b{

hvar myVar = "hello world"

}c

} {

wrap(debug(myVar))

}

The preloop property runs arbitrary script code by compiling the provided code block into a delegate (similar to VTP and GCXF) and executing it. It runs this delegate once before each repeater loop. Similarly, there also exist start (run before all repeater loops), postloop (run once after each repeater loop), and end (run after all repeater loops). In addition, we can also use the exec StateMachine to run arbitrary code at any point. (exec can also be an AsyncPattern or SyncPattern.) The argument type of all of these methods is ErasedGCXF, which is similar to GCXF<T> except its return value is ignored.

gtr {

wait(60)

times(4)

} {

//This would function the same if it was in preloop.

exec(b{

hvar total = 0;

for (var ii = 0; ii <= i + 1; ++ii) {

total += ii;

}

total;

})

sync "arrow-red/w" <> gsr {

times(total)

circle

} s rvelocity cx 2

}

This script fires 1 bullet, then 3 bullets, then 6 bullets, then 10 bullets.

Dynamic Scoping

Consider this basic script, which fires some bullets that are destroyed after moving for 1 second.

paction 0 {

bulletcontrol persist "circle-green/w" softcull(null, t > 1)

async "circle-green/w" <> gcr2 30 inf <> {

} gsr2c 10 {

preloop b{

hvar loop = i

}

} s rvelocity px 2

}

As with VTP and GCXF, the second argument to softcull is compiled into a delegate, though this is done on the backend and isn't shown in the type signature.

Let's say we also want to restrict the bullet control so it only affects bullets that have a certain value of loop. While we ideally should be able to do this, loop is not lexically visible to the bullet control function. Also, even if loop was lexically visible, there isn't a guarantee that it would be the correct loop, since bullet controls can affect bullets fired by other scripts. To resolve this, DMK allows dynamic scoping within bullet controls. We dynamically access the variable by writing it as &loop, and the backend will crawl up the bullet's environment frame to look for any occurrence of the variable.

paction 0 {

bulletcontrol persist "circle-green/w" softcull(null, t > 1 & &loop == 8.0)

async "circle-green/w" <> gcr2 30 inf <> {

} gsr2c 10 {

preloop b{

hvar loop = i

}

} s rvelocity px 2

}

When using dynamic variable access, the type of the referenced variable cannot be determined based on its occurence elsewhere in the script. In the above example, &loop is determined to be a float because it is compared to 8.0. However, if the typechecker cannot auto-determine the type of the referenced variable, then you can provide a type annotation (eg. &loop::float == 8).

When using dynamic variable access, it is possible to reference a variable that does not exist. For example, if we write &loooop == 8.0 instead, then the script will compile and run, and then produce a runtime error after 1 second (when the first bullet passes the t > 1 condition). If the type of the dynamic variable access is incorrect, then it will also produce a runtime error (eg. (&loop::Vector2).magnitude == 8.0).

It is possible for some bullets to have the variable provided, and for others to not have it provided. For example, if we added sync "circle-green/w" <> s rvelocity cy -4 to the above code, then the bullet fired by this command would produce a runtime error after 1 second, even if the bullets fired by the async command wouldn't produce any errors.

Dynamic variable access can read and write the actual variables in the environment frame (there is no caching or freezing behavior in the way). For example, the below example uses the exec bullet control to modify a variable every time the bullet control is executed.

paction 0 {

bulletcontrol persist "circle-green/w" exec(b{

&size = &size + 1f

}, _)

async "circle-*/w" <> gcr2 24 inf <3> {

preloop b{

hvar size = 1 //shared between red and green!

}

} gsr2c 2 {

color { "red", "green" }

preloop b{

//if we move hvar size = 1 here, then it won't be shared

}

} simple rvelocity px 2 {

scale(size)

}

}

In this example, the bullet control modifies the size variable, which is declared in the gcr preloop property. Since it is declared in the gcr preloop property, it is shared by both the red and green bullets. Thus, the size of the red bullets also increase, even though the bullet control only affects the green bullets.

If we move the declaration of size down to the gsr preloop property, then it will no longer be shared by the red and green bullets, and only the green bullet will get larger.

(Note that in BDSL, 1f is 1/120. f is a multiplier for the seconds-per-frame of the engine, which is 1/120, since the engine internally runs at 120 FPS. The bullet control is run once per frame, so it increases size by 1 per second.)

Within a dynamic scope like bullet controls, functions must also be dynamically accessed by prefixing them with &. The function must be lexically visible to the bullet control. If by some chance the control is executed on a bullet to which the function is not lexically visible, then it will throw a runtime exception.

function deltaSize(size::float) {

return size + 1f;

}

paction 0 {

bulletcontrol persist "circle-green/w" exec(b{

&size = &deltaSize(&size)

}, _)

async "circle-*/w" <> gcr2 24 inf <3> {

preloop b{

hvar size = 1 //shared between red and green!

}

} gsr2c 2 {

color { "red", "green" }

} simple rvelocity px 2 {

scale(size)

}

}

Note that dynamic function lookup is slower than constant function lookup, so if possible, we should declare the function as const, and then we do not need to prefix it with &. Likewise, if we need to reference any top-level scripting variables within the bullet control, we should ideally declare them as const as well, and we do not need to prefix them with &.

const function deltaSize(size::float) {

return size + 1f;

}

paction 0 {

bulletcontrol persist "circle-green/w" exec(b{

&size = deltaSize(&size)

}, _)

async "circle-*/w" <> gcr2 24 inf <3> {

preloop b{

hvar size = 1 //shared between red and green!

}

} gsr2c 2 {

color { "red", "green" }

} simple rvelocity px 2 {

scale(size)

}

}

Imported functions and variables do not require any special prefixing in dynamic scopes, regardless of whether or not they are constant.

Environment Frames

For the most part, variable access and scoping is handled via environment frames. For a given lexical scope, a new environment frame is created every time the lexical scope is entered, using the existing environment frame as a parent. This logic is broadly applicable across most modern programming languages.

As an example, consider the following C# code, or its equivalent in any Java-like langauge.

var total = 0;

for (var ii = 0; ii < 5; ++ii) {

var y = ii + 1;

total += y;

}

return total;

In the code above, there are three lexical scopes: the outermost scope (containing total), the scope for the for initializer (containing ii), and the scope for the for loop body (containing y). The outermost scope and the for initializer are entered only once, so they each create only one environment frame. The for loop body is entered five times, so it creates five environment frames.

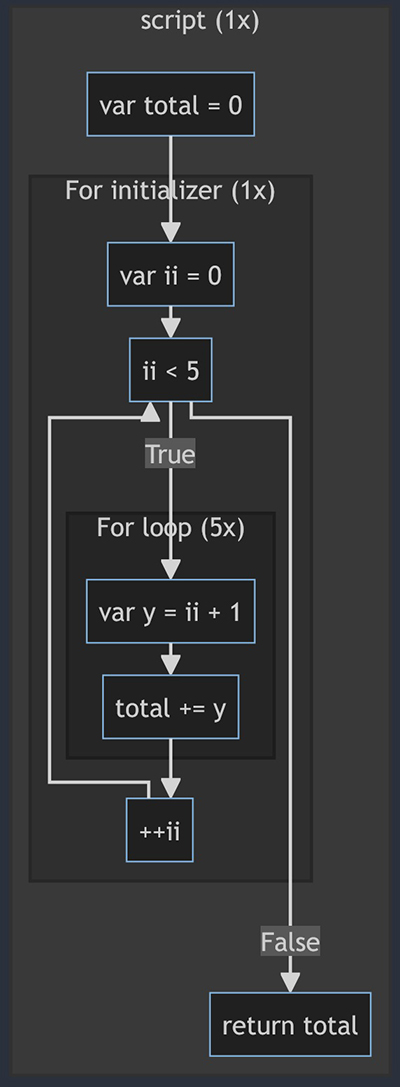

The diagram above shows the execution pathway of the code. Each nested dark block represents a lexical scope. When entering a scope, an environment frame is created, and when leaving a scope, that environment frame is destroyed (if it is not captured in a lambda of any kind).

When in the innermost lexical scope (the for loop scope), we can access ii and total, even though they are not stored in that scope's environment frame. The language does this by looking in the ancestors of the current scope's environment frame.

Note that the fact that ii is shared between loops means that loops are not independent of each other. Consider the following C# code, or its equivalent in any Java-like language:

var lambdas = new Func<int>[5];

for (int ii = 0; ii < 5; ++ii)

lambdas[ii] = () => ii;

foreach (var l in lambdas)

Console.WriteLine(l());

If we run this code, it will print "5" to the console 5 times. This behavior is problematic for asynchronous behavior, as used in GXR repeaters. Ideally, we want the value of ii to be preserved for every loop, even if they are running code asynchronously. Thus, the environment frame logic for GXR repeaters is slightly different: there is no separate lexical scope for the initializer, and instead, variables are copied between iterations. Consider the following StateMachine code:

var speed = 2;

async "circle-green/w" <> gcr2 60 inf <> {

start b{

hvar angl = 0

}

postloop b{

angl += 90;

}

} s rvelocity(rotate(angl, px(speed)))

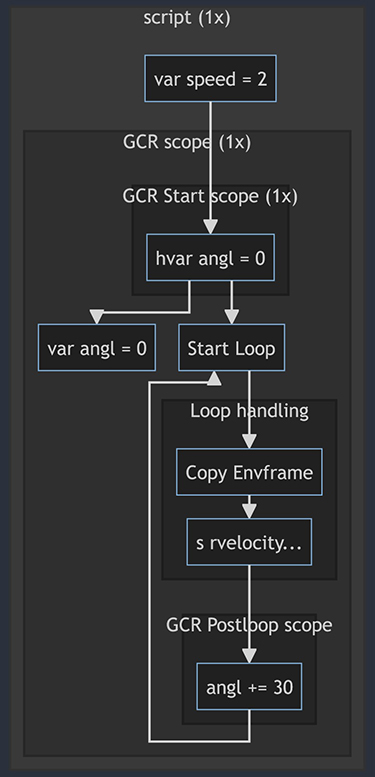

This code fires bullets and increments the angle of fire by 90º between fires. However, previous bullets are not affected when the angle is incremented. Consider the execution pathway diagram for what occurs at runtime:

In addition to the script scope and the GCR scope, there are also the GCR start and GCR postloop scopes, but there is no scope for the GCR loop itself. Instead, at the start of the GCR loop, the current envframe is copied before passing it to the child commands (s rvelocity...). Since the bullet is using the copied envframe and the postloop command modifies the original envframe, the bullet isn't affected by any postloop calls after it is created.

To further illustrate why this matters, let's extend the code:

var speed = 2;

paction 0 {

position 0 0

async "circle-*/w" <> gir2 200 inf <> {

start b{

hvar angl = 0

}

postloop b{

angl += 90;

}

color({ "red", "green", "blue", "yellow" })

} gcr {

wait 50

times 4

postloop b{

angl += 14;

}

} s rvelocity(rotate(angl, px(speed)))

}

Now, we are firing a nested asynchronous pattern. In the outer repeater, we increment angl by 90 every iteration, and in the inner repeater, we increment angl by 14 every iteration. Each group of four bullets fired by the inner gcr repeater share the same angl value, because angl is stored in the per-iteration copied envframe of the outer gir repeater. Thus, when the second bullet in the inner repeater is fired, the first bullet's angl changes. However, the value of angl is not shared across iterations of the outer repeater, since each iteration copies the repeater's environment frame before starting. As a result, each group of four bullets is independent of other groups.