UI Design Document (DMK v9.0.0)

Creating a Navigable Layout

The DMK UI architecture places a heavy emphasis on the ability to navigate menus with both keyboard and mouse input. Keyboard input requires a strict UI layout to allow efficient navigation via arrow keys and Confirm/Back keys, whereas mouse input requires all visible nodes to be trivially accessible from each other, which is better served if the layout is unstructured. As such, these requirements have somewhat contradictory impulses.

First, let us define some terms:

- (UI) node refers to anything on the screen that can be selected by the cursor.

- (UI) layout refers to the abstract net of relationships between UI nodes. For example, the relationship of "pressing Right when the cursor is on Node A will move the cursor to Node B" is part of the layout. The question of how these relationships are rendered is not part of the layout. For example, the display could place Node A in the bottom-right corner of the screen and Node B in the top-left corner, and this would not be part of the layout (it would be part of the HTML).

- HTML refers to how nodes and other unselectable objects are rendered on screen. (Strictly speaking, it is called UXML/USS in Unity, and no browsers are involved, but it is, for all intents and purposes, a Unity implementation of HTML/CSS.)

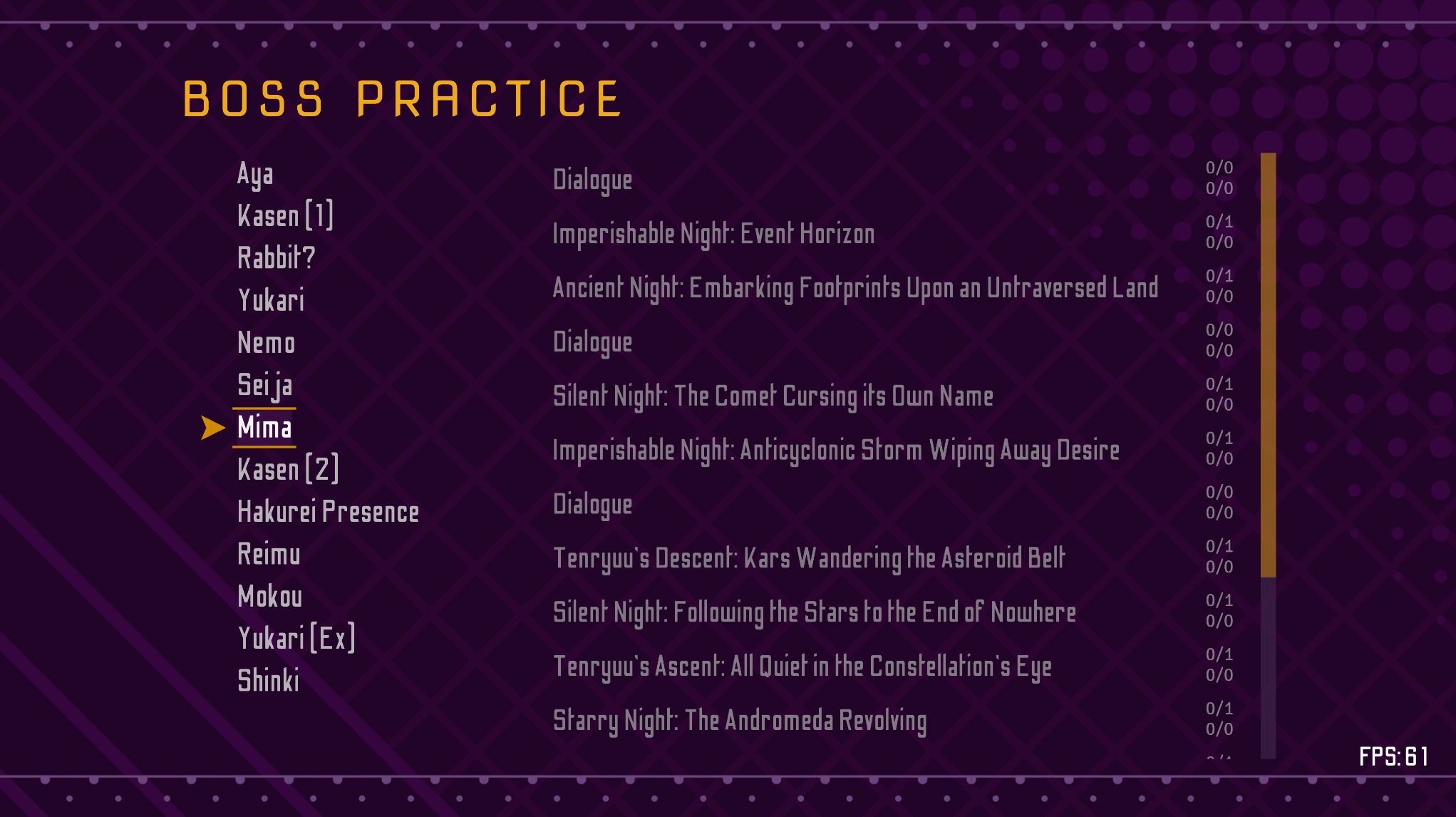

Let us examine how we might create an efficiently navigable UI layout. Our first approach might be to make the UI layout correspond to the HTML, which is how a standard browser would automate layout handling. However, this approach runs into contradictions for many common use-cases. Consider the boss practice menu: the left column displays a list of bosses, and for whichever boss is currently selected, a list of their spellcards appears in the right column.

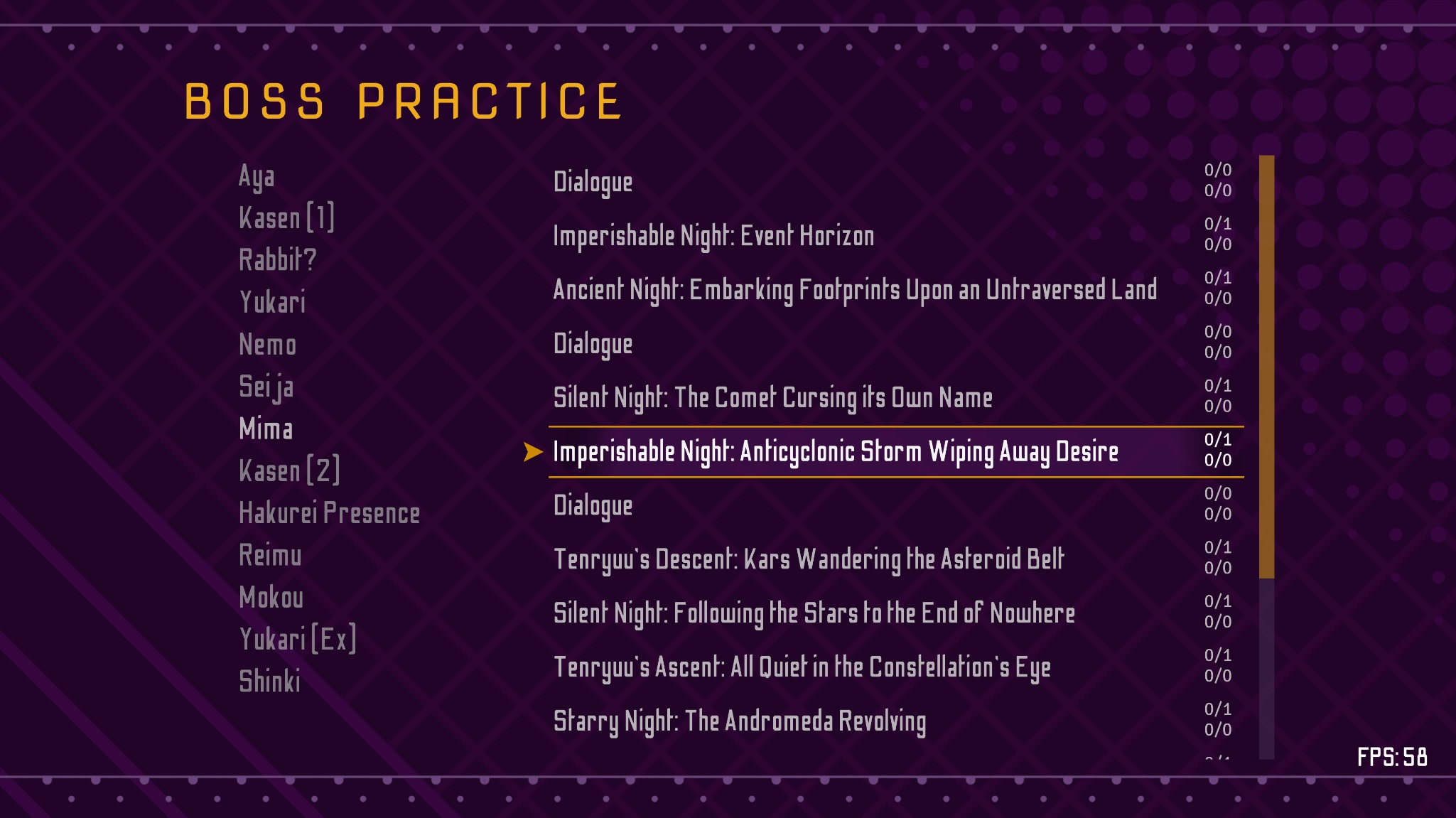

In this case, we have two separate columns. Each column can be navigated on its own with up/down keys, and this requires no special consideration. However, matters become more complex when we consider what happens when moving between the columns. If we press Right or Confirm from an entry in the left column, the current selection moves to the right column:

Now that we are in the right column, there is a common-sense layout requirement that pressing Left or Back should return us to the node in the left column we came from (here "Mima"). We can encode this layout behavior either statically-- by encoding in the layout that "Mima" is a parent of the current set of nodes on the right-- or dynamically-- by recording a stack of group-to-group transitions, and simply popping from the stack to reverse a transition. The dynamic strategy works for this use-case, but does not work for other cases that involve moving between groups of nodes. For example, consider the Game Results screen in DMK.

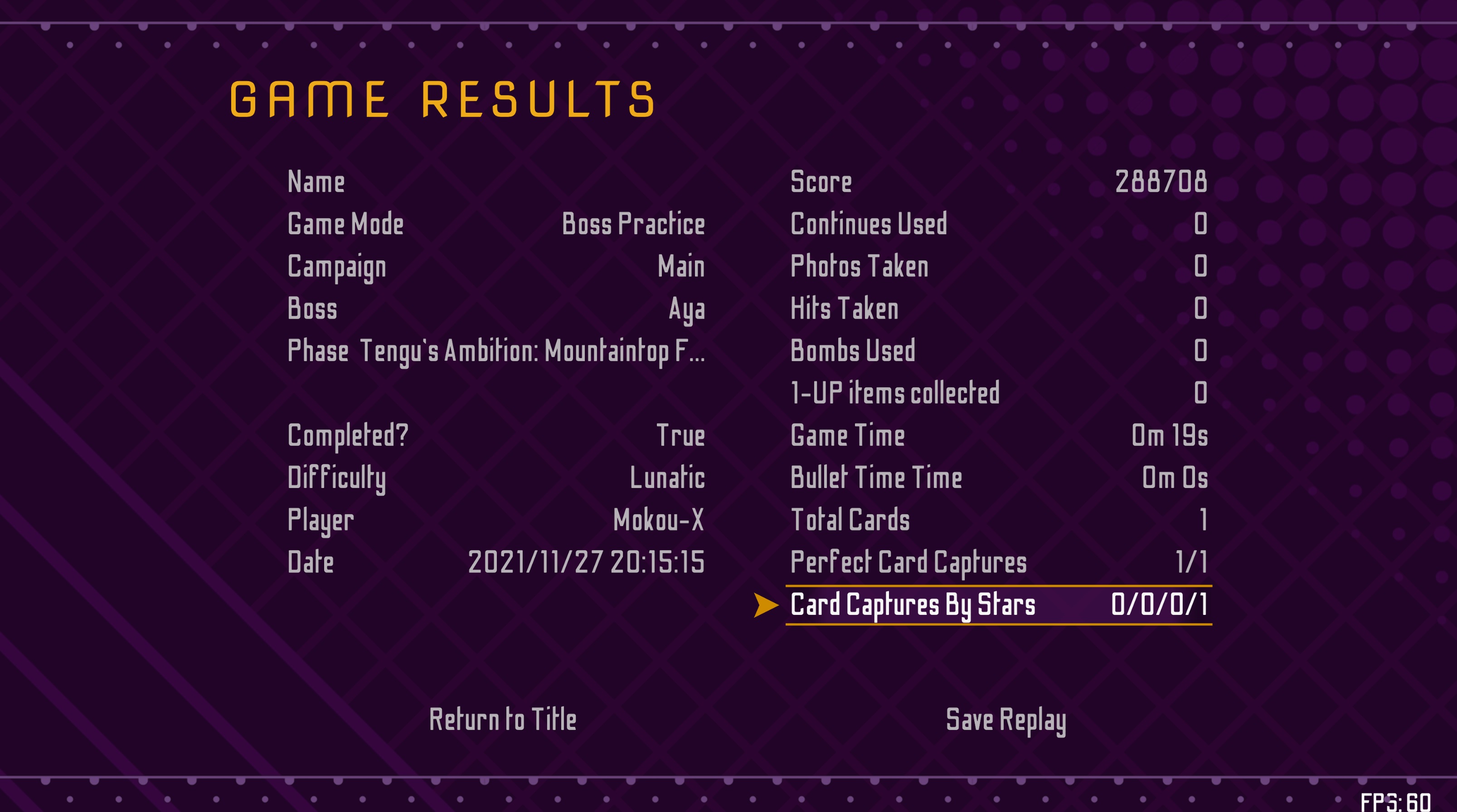

This screen has three "groups": a row at the bottom that can be navigated with left/right input, a column on the right (in which the cursor is contained) that can be navigated with up/down input, and a column on the left that can be navigated with up/down input. From the cursor, if we press Down, the cursor should move to the bottom row, preferably the "Save Replay" node. If we instead press Left, the cursor should move to the left column. Note that pressing Confirm should do nothing, unlike the boss practice screen.

Let's say we press Left, and the cursor moves to "Date". Here, we have made a group-to-group transition, but there is no need to store the transition on the stack. If, from "Date", I press Back, then from a UX perspective I expect the cursor to move to "Return to Title", not "Card Captures By Stars". For the sake of thoroughness, let's say that we decide to encode such functionality despite the UX concern. If we then press Down to create a transition to the bottom row, then press Right and then Up to create a transition to "Card Captures By Stars" once again, we have made a triangle of transitions that ends up in the same place. Now, if we press Back three times, we will end up at the same "Card Captures By Stars". Storing group-to-group transitions (dynamic encoding) results in such necessary but undesirable behavior when it comes to Back button functionality.

Given the above concerns, the UI architecture prefers to encode relationships between groups statically. In the boss practice screen, the group of nodes on the right are a child of the "Mima" node, and that static information can be used to guide the behavior of Back. On the game results screen, the three groups are siblings, and therefore Back does not reverse transitions between them. (This is a simplified picture that we will develop further below.)

Observe that on the boss practice screen, the two columns in HTML cannot have a parent/child relationship (since that would require placing one column within the other). However, the nodes in the columns must have a parent/child relationship in the layout. As a result, it is impossible to unify layout relationships with HTML relationships.

The Three Core Abstractions

The above discussion allows us to create the three core abstractions of the UI architecture. The first abstraction is UINode, which simply describes nodes. The layout relationships of a UINode are determined by its containing UIGroup. For example, if a UINode is part of a UIColumn (a subclass of UIGroup), then pressing Up or Down should move the cursor up or down within that column, but if a UINode is instead part of UIRow (a subclass of UIGroup), then Left or Right would move the cursor around within the group. While individual UINodes know how to create their own HTML renderings, the question of where in the screen's HTML tree they should be rendered is determined by the containing UIGroup. The logic for this HTML handling is contained within the third abstraction: UIRenderSpace, which points to some element in the screen's HTML tree. Each UIGroup links to exactly one UIRenderSpace, but multiple UIGroups may link to the same UIRenderSpace.

For simplicity, these three abstractions will hereafter be referred to as nodes, groups, and render spaces.

Let us now examine how we can encode the layouts for the boss practice and game results screens.

Show/Hide Group

For the boss practice screen, there is one column group, pointing at the left column render space, containing all the boss name nodes. Then, for each boss name node, there is a column group containing the boss spellcard nodes, pointing at the right column render space. When a boss name node is selected by the cursor, the corresponding spellcard group appears, and when that boss name node is deselected, that group disappears. This relationship, where the visibility of one group is dependent on whether or not another node is selected, is encoded as the UINode property ShowHideGroup. If a Node A in Group 1 has ShowHideGroup set to Group 2, then Group 2 is a child of Group 1, providing the necessary Back button behavior.

Composite Groups

When a node is in a column group, pressing Up or Down moves to a different node in the column. This behavior must be encoded in the group, since it varies by the type of the group (eg. column vs. row) as well as the other nodes in the group (of which the node in question is unaware).

However, pressing navigation keys may move the cursor out of the group. In a normal column, such as the boss name column in the boss practice screen, pressing Down on the lowermost node ("Shinki") loops back to the top of the column ("Aya"), or it could be coded to instead do nothing. However, on the game results screen, if we press Down from "Card Captures by Stars" (the lowermost node in the right column group), then instead of looping to the top of the right column group ("Score") or doing nothing, the cursor should move to "Save Replay" in the bottom row. This layout relationship between the groups also needs to be encoded somewhere.

While we could manually wire together these groups, the most generalizable way to handle this is to allow groups to contain groups. CompositeUIGroup, a subtype of UIGroup, is the base class for groups that contains other groups. For the game results screen, we use the subclass LRBGroup, which is a CompositeGroup that contains a left group, a right group, and a bottom group. Composite groups encode relationships between their component groups. They do not need to know what type of groups their component groups are (ie. whether they are columns or rows or something else). For example, consider what happens when we press Down on "Card Captures by Stars". This takes the cursor out of bounds of the right column group, and the fallback behavior is to loop back to the topmost node. However, before looping back to the top, the right column group will try to defer navigation to its parent group (LRBGroup). In this case, LRBGroup knows that the bottom group is below the right group, so it tells the cursor to go to the bottom group (containing "Return to Title" and "Save Replay"). In this example, it does not matter that the bottom group is a row and the right group is a column; all that matters is that navigation has taken the cursor out of bounds of the right group in the downwards direction.

Navigation is only deferred to the parent when it takes the cursor out of bounds of the group. For example, if we pressed Up on "Card Captures by Stars", then the right column group would move the cursor to "Perfect Card Captures" without deferring any navigation to its parent group.

When any node in a composite group is selected by the cursor (the "Focused" state), all nodes in that group are displayed in a highly visible state (specifically, the "GroupFocused" state). This behavior differs from ShowHideGroup. In the first screenshot, the nodes in the right column are displayed in a low visibility state (specifically, the "Visible" state). This behavior was chosen as the most reasonable interpretation of how show/hide groups and composite groups should be rendered.

Note: While it may sound suspicious to encode CompositeUIGroup as a subtype of UIGroup rather than a distinct abstraction given that CompositeUIGroup cannot contain nodes, it works much more cleanly with parenting relations, as well as with managing control flow (to be discussed further below).

Group Call Stack

Recall that when we press Back, the cursor should return to the node that it originated from, but only in hierarchical cases like with Show/HideGroup, and not with sibling cases like CompositeGroup. Also note that since parenting relations are between groups, the specific node that caused the cursor to move from a parent group to a child group is not known statically.

The runtime information of what hierarchical sequence of nodes produced the current cursor is stored in the Group Call Stack, which has type Stack<(UIGroup, UINode?)>. As elements are only pushed to this stack in group-hierarchical order, the UIGroup element is technically redundant, and could be computed from the selected node's group's hierarchy information. However, storing it in the stack makes some operations simpler. The UINode element is null in CompositeGroup cases, since it is easier to store than to ignore composite groups in the group hierarchy, even if they do not involve nodes. For example, in the case where we are on "Card Captures by Stars" on the game results screen, the group call stack contains one element: a tuple of the LRBGroup composite group, and a null UINode. In fact, no matter what node we have selected on the game results screen, the group call stack contains only that one element.

As another example, in the second screenshot of the boss practice screen, the group call stack contains one element: a tuple of the boss name group and the "Mima" node.

When we move between nodes in different groups, we need to know which groups we left and which groups we entered. Let us assign letters to groups, and denote a group hierarchy as A.B.C when A is a child of B and B is a child of C and C has no parent. Let's say the current node's group has a hierarchy of A.B.C.X.Y, and we want to move to a node with hierarchy D.E.X.Y. In this case, the group hierarchies form a Y shape:

A - B - C

\

X - Y

/

D - E

In this case, we want to leave groups A, B, and C, and then enter groups D and E. We can compute left and entered groups with some basic linked list analysis between the source node's group's hierarchy and the target node's group's hierarchy. This approach allows us to instantly move between arbitrary nodes, so it gives us full mouse navigation support.

Sometimes, we want to simply return to the group caller, such as when pressing Back. To do this, we pop from the group stack until we find an entry with a non-null node, and the cursor goes to that node.

Sometimes, we want to return to any node in a given group. For example, given A.B.C.D.E, we may receive a command of the form "return to C". To do this, we pop from the group stack until we find the entry with the corresponding group, and the cursor goes to the paired node.

Screens

The above discussion is sufficient to describe the behavior of UI layouts on any single screen. However, menus are often composed of different screens that can be accessed from one another. The common-sense layout requirement is that if we press Back on a node whose group does not have a parent (such as "Mima" on the boss practice screen), then we should return to the node on the previous screen.

Relationships between screens are non-hierarchical. The control system stores a Screen Call Stack which works similarly to the group call stack, but it has no hierarchy requirements, and would theoretically record loops of calls if two screens repeatedly called each other, as in the discussion of dynamic group-to-group transitions. (There are exceedingly few reasonable situations where it is possible for two screens to be able to access each other, and I have not run into any.) We then encode a fallback behavior in UIGroup that attempts to pop from the screen call stack when Back is pressed and the group parent does not exist or does not specify a node to go to.

UIScreen is the fourth and final abstraction in the UI architecture. It contains a set of groups (each group is assigned to exactly one screen). In DMK, all screens use the same base HTML, which contains a header, a container, and a shadow that dims the entire screen when active. The header is filled with text provided as a constructor argument. Any further structures within the container can be created at runtime via the Builder property, and the groups can render their nodes to any HTML entry that is a descendant of the screen HTML, though in all existing cases except popups (below), they render to some descendant of the container. Screens may also link to a background (specifically, a dynamic background that renders to WallCamera-- the same backgrounds that are manipulated during normal gameplay), and when the screen is entered, the WallCamera will switch to that background.

Popups

Popups contain incredibly complex logic, but can be handled with just the abstractions discussed above. Before we discuss the architecture, let's examine the common-sense layout requirements around popups.

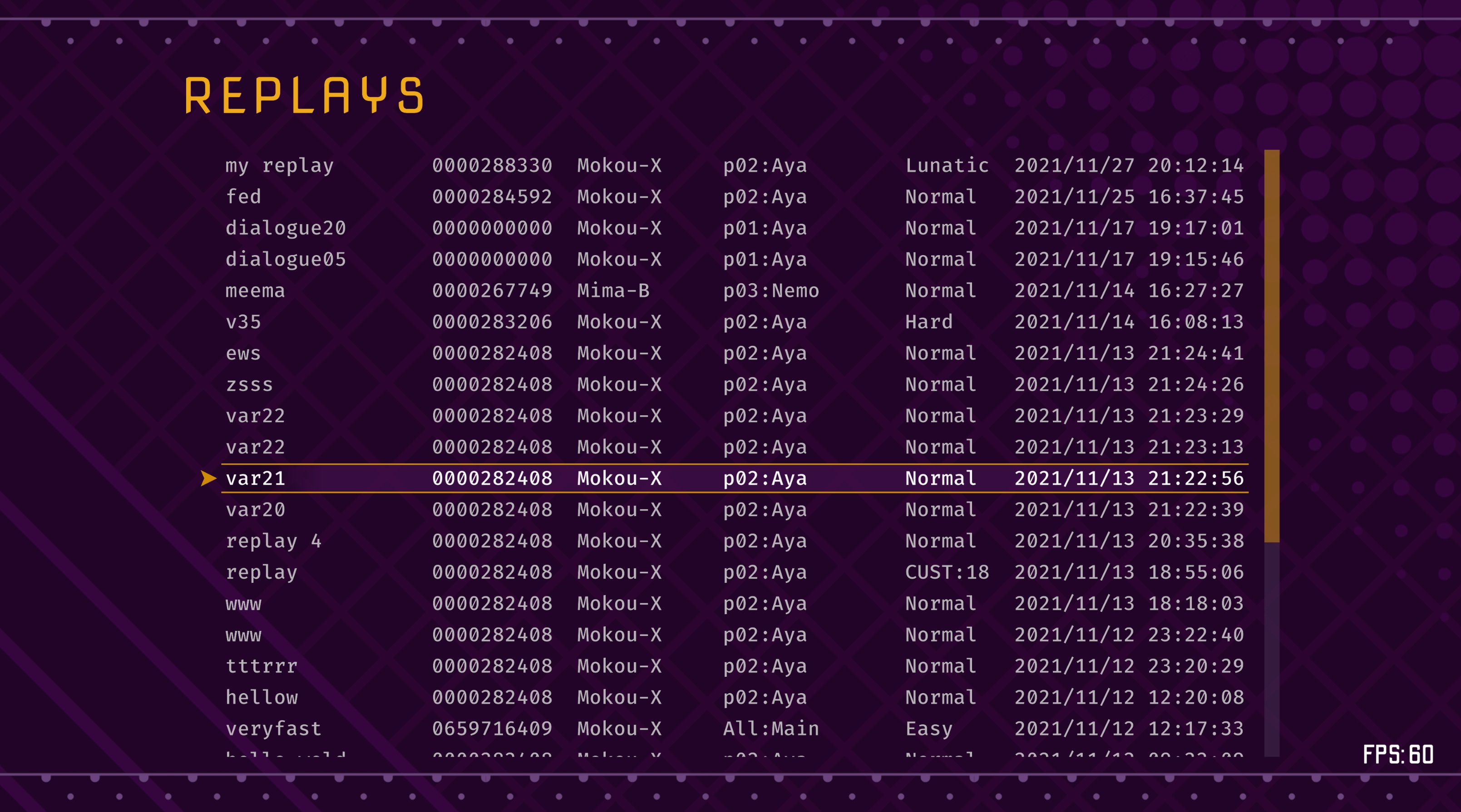

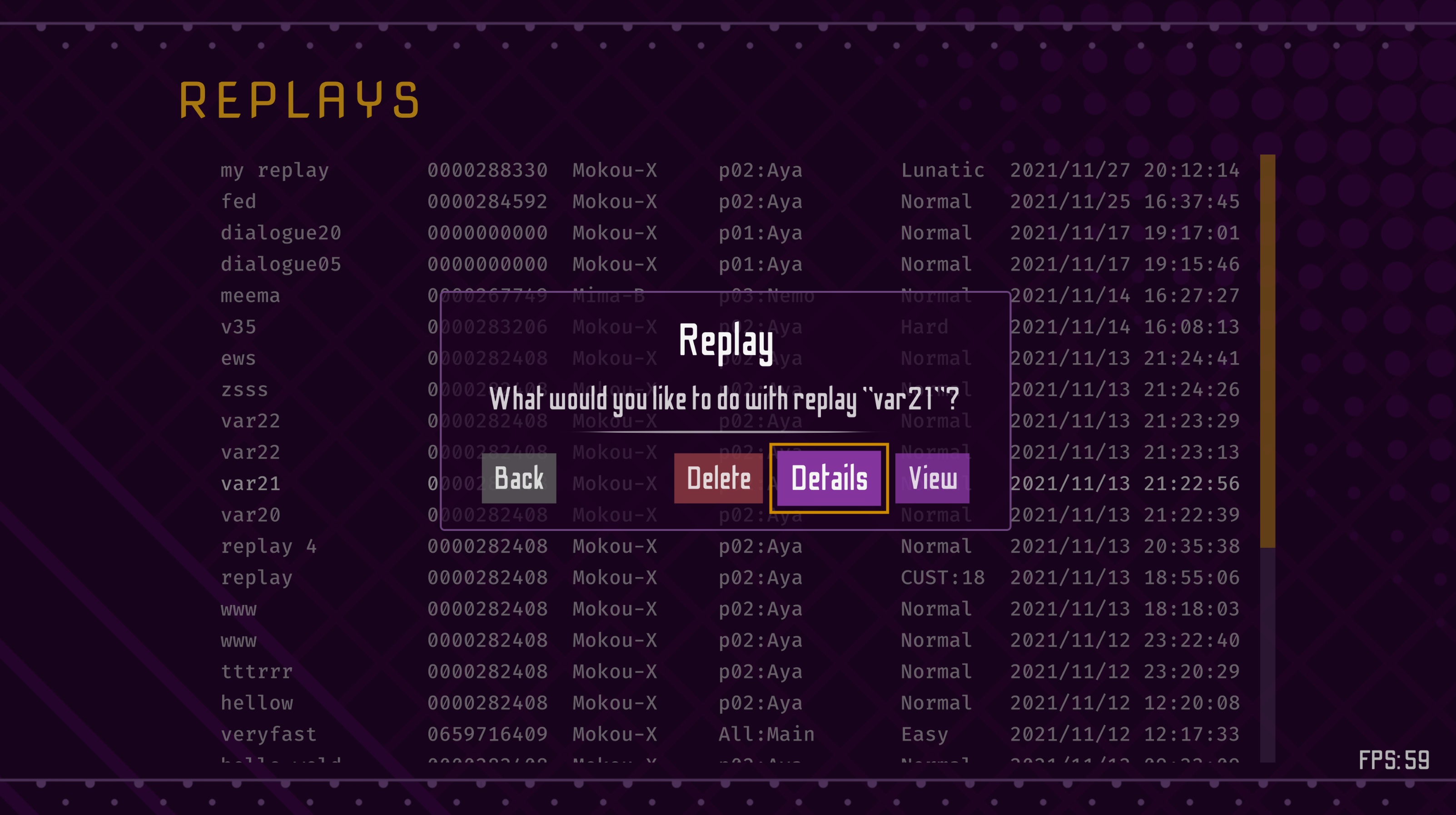

Let's start with the replays screen. This screen has a single column group with one node for each saved replay. In the screenshot below, the group call stack is empty.

If we press Confirm on this node, a popup should be dynamically generated containing content related to this replay. The position of the popup should be absolute (in the CSS sense), and when it appears, the rest of the screen should dim a bit. When leaving the popup, it should be destroyed. To achieve this, we will consider the popup as a group (PopupUIGroup) that is dynamically and temporarily added to the screen, and we will render it under the screen's shadow.

Note how the node we came from ("var21") is highlighted, and if we press the "Back" button, we should return to "var21". This requires that the popup is a child of the column group. When we create a popup, we attach it as a child to the group of the node that constructed it, and we push that group and that node to the group call stack.

You might expect that, in the second screenshot, the group call stack has one entry with the column group and "var21". While this entry is in the stack, there are also more entries. In order to maximally generalize the possible contents of a popup, the popup group is itself a composite group that contains just a header string ("Replay") and then a body group. In this case, the composite group must not only include the row of buttons at the bottom, but also the displayed content in the middle of the popup ("What would you like to do..."). Note that we cannot assume that the content in the middle of the popup is uninteractable, or that it has a fixed format. Consider the game results screen, where pressing Confirm on "Save Replay" brings up a popup where the user must navigate to content in the middle of the popup and interact with it.

Therefore, in the case of the replay popup, the popup group is a composite group with a single component group. This component group is a "vertical composite group", which handles any number of component groups oriented along a vertical axis. The vertical composite group has two component groups: a column with a single node ("What would you like to do..."), and a row with a set of options.

Let the replay column group be A, the popup group be B, the popup body group be C, the popup body column group be D, and the popup body row group be E. Then, on the replay screen popup, while the cursor is on the Details button, the group call stack contains the following elements, from oldest to youngest:

- Group A (hierarchy A), node "var21"

- Group B (hierarchy B.A), null node

- Group C (hierarchy C.B.A), null node

and the current node is "Details" with hierarchy E.C.B.A.

When we press the "Back" button, we issue a "return to Group A" command. As soon as B is exited, the popup HTML destroys itself.

When we press the "Details" button, we issue a command that first returns to Group A (causing the popup to destroy itself) and then moves to the game details screen.

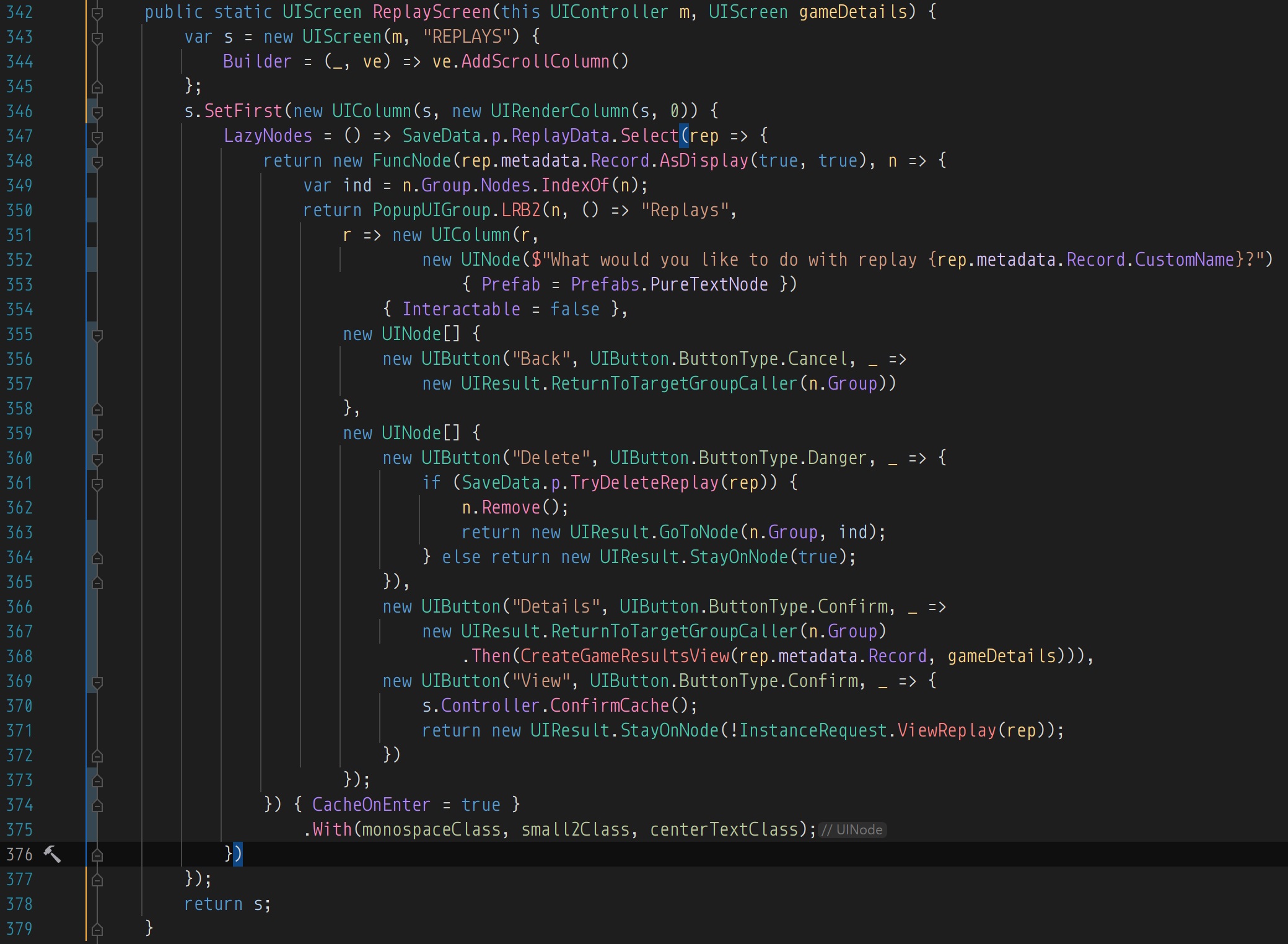

To see how this all comes together, let's examine the code that constructs the replays screen.

Case Study

The code that creates the replay screen is shown below.

Let's proceed through this code line by line.

Lines 343-345 create the replay screen. "REPLAYS" is the title that displays at the top. The Builder property determines what extra HTML content is added to the base screen HTML. In this case, we need one column to display all the replays, so we add one scroll column using an extension method.

Then, we create the replay column using new UIColumn. The first argument to the constructor is the enclosing screen, and the second argument is the render space for the group. UIRenderColumn is a subclass of UIRenderSpace that targets columns in the HTML tree. new UIRenderColumn(s, 0) means "target the first (0th) column in the container of screen s".

We also call s.SetFirst. If a screen is entered without explicitly naming which node or group the cursor should go to, it will default to the first group in the screen. As the order of group additions may be unpredictable due to how nested execution works, it is generally a good idea to explicitly designate which group is the "first" group using SetFirst.

Normally, the nodes in a group are provided as a params UINode[] argument to the group constructor. However, there are cases where the information that populates nodes is slow to construct; in the case of replays, displaying information about a replay requires parsing all game scripts covered by that replay. In order to minimize initial game startup time, we can lazily construct the nodes by providing them as a LazyNodes property.

The LazyNodes property constructs a FuncNode (line 348) for each replay in SaveData.p.ReplayData. A FuncNode is a node that executes a function when the user inputs Confirm while selecting it. The first argument to the constructor is the display string, and the second argument is a Func<UINode, UIResult> that is executed on Confirm. In this case, the returned UIResult is a dynamically-constructed popup group, constructed by the helper function LRB2. A UIGroup is implicitly converted to a UIResult as "move the cursor to the entry node of this group".

LRB2 (line 350) is a helper function for the common popup use-case of having some kind of inner body in the center of the popup and a row of options at the bottom of the popup, some of which are left-flush and some of which are right-flush. The first argument (line 350) is the source node, which is how the popup group knows which group to take as a parent. The second argument (line 350) is a Func<LocalizedString> that returns the header text. The third argument (line 351) is a function that, given a UIRenderSpace pointing to the inner body of the popup, constructs a UIGroup in that inner body. In this case, we have a column of one node, and that group is not interactable. The fourth argument (line 355) is a list of left-flush options in the bottom row. We only have the "Back" option, which returns a result of "return to the group of the source node" when clicked.

The final argument (line 359) is a list of right-flush options in the bottom row. The first option is "Delete", which attempts to delete the replay, and if it succeeds, deletes the source node as well. Once the source node is deleted, it would be incorrect to use ReturnToTargetGroupCaller since that would result in returning to the deleted node present on the call stack, so we instead go to the i'th node in the replay column group, where i is the original index of the source node. If the deletion fails, we return a no-op. The second option is "Details", which first returns to the source node, and then transitions to the game results screen, which is populated with the replay data. The final option is "View", which returns a no-op, but calls ViewReplay, which transitions the Unity scene (and therefore destroys the entire menu). In general, when Confirming a node performs an operation that changes the Unity scene, the returned UIResult is simply a no-op for simplicity.

Menus have support for a limited degree of caching behavior. A node that has the property CacheOnEnter set to true (all the replay nodes, line 374) will tentatively cache its position as a static property (in the C# sense) on the containing menu class. Then, a function that transitions the Unity scene can call ConfirmCache to finalize this cache. When the menu is loaded again, it will try to restore the position that was cached.

The .With function on nodes (line 375) applies CSS classes. In this case, we want the replay descriptions to be small monospaced center-aligned text.

Conclusion

The most well-known existing form of UI handling-- HTML/CSS in the browser-- is designed almost exclusively for mouse-based traversal, and does not support the kind of keyboard-only traversal we need for a video game-oriented UI. Furthermore, I do not know of any well-documented keyboard-only UIs. As a result, the design here may seem unusual compared to other instances of UI design.

There are some uncertainties around certain points in the design here. The largest is around the usage of the Group class for composite group handling. It may be cleaner to use a different abstraction, especially given that composite groups introduce nullability into the group call stack. In addition, it is unclear whether show/hide groups, popups, and composite groups should be using the same hierarchy system, since they have different display configurations and layouts. Finally, the handling for multiple screens may not be sufficient for use-cases where movement between screens is much more heavily emphasized.